Narnia0

by Koosha

In this post I’m going to share my write-up for the first level of Narnia series of challenges from OvertheWire. This post is not just a CTF write-up, but an excuse to learn about computers and security. A base knowledge of Linux operating system, programming (Especially in C) and Assembly Language is needed. Enjoy! :)

All files related to the challenges are listed in /narnia/ directory on the server. One narniaX.c for source code and one narniaX as the compiled executable version, for each level of number X.

First we look at the related concepts and then analyze the source line by line.

Initial Inspection

file & ls

Almost always the first commands to use are find and ls -l. Let’s see what initial details narnia0 binary has:

$>file narnia0

narnia0: setuid ELF 32-bit LSB executable, ...

From above we learn that it is a 32-bit executable Linux binary. So far a lot if info!

$>ls -l narnia0

-r-sr-x--- 1 narnia1 narnia0 7456 Aug 26 2019 narnia0

ls shows that we (as a member of group narnia0) have reading and execution access to the binary. So we can not change it!

Also a setuid bit is set, meaning when we execute narnia0 it will be executed with narnia1 user access. Important detail!

CCC (C Calling Convention)

In order to understand the assembly code of the program we need to familiarize ourselves with the concept of C calling convention.

What does it mean? For the subroutines in the program to be executed there is a convention to be followed, a set of rules.

It’s divided into two sets. Rules which the caller should obey them and rules which the subroutine itself (I.e calle) must follow.

We look at them nice and brief:

Notes:

- The ESP register always points to the top of the stack.

- Stack grows down! Stack grows from up to down, meaning every new value which is entered with the push command lies down in a lower address, so the next entering value would be beneath it. Look up here for more details.

- Conventions are different in 32-bit and 64-bit architectures. We consider the 32-bit version in this post, since we have a 32-bit binary.

Caller’s Convention

In each convention there are two fazes which are mirrors to each other. One undoing what the other did:

- Prologue

| Stage | What to do? | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Save the registers! | Save the contents of registers EAX, ECX, EDX If you want to preserve them. You can restore them after the function call. Now push them on the stack! |

| 2 | Pass the parameters! | Push the parameters of the subroutine onto the stack, in the reversed order (stack grows down). |

| 3 | Call! | Call the subroutine using call instruction. This will place the return address on top of the parameters on the stack. |

- Epilogue

| Stage | What to do? | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Remove the parameters | Remove the parameters from the stack, restoring it to the previous state. This is done by adding the proper value (Number of bytes used by the parameters)to the ESP. E.g: If they were three integers (4 bytes each): addl $12, %esp |

| 2 | Check the EAX! | The return value of the subroutine can be found in the EAX register. |

| 3 | Restore the Regs! | Restore the registers by popping them off the stack. |

Callee’s Convention

- Prologue

| Stage | What to do? | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Push EBP | Push the EBP register on the stack. This way EBP is a point of reference to other values near it like parameters and local variables. This way we also preserve the contents of EBP. |

| 2 | movl %esp , %ebp |

Move ESP’s content into EBP, so we have the reference address to work with. Now EBP points to the value of Old EBP. |

| 3 | Make space for the variables! | Allocate local variables by making space on the stack. This is done by subtracting the required value from ESP register. E.g for allocating 3 integers (4 bytes each) we do this: subl $12, %esp |

| 4 | Save the Registers! (again?!) | Save the callee’s registers including EBX, EDI and ESI. These are the ones needed to be saved by the function. |

| 5 | Return in EAX | When the function is done, return the exit value in EAX. |

- Epilogue

| Stage | What to do? | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Restore the Regs! | Restore the saved registers by popping them off the stack. |

| 2 | Deallocate those vars! | Deallocate the space made for variables by the moving base pointer’s value into the stack pointer: movl %ebp, %esp. Smart ha?! It works because EBP has the initial value of ESP before allocating variables’ space. |

| 3 | Restore the poor EBP! | Finally undo the first act, restore the base pointer by popping the old EBP off the stack. |

| 4 | Ret! | Return to the caller by executing the ret instruction. This instruction will find and remove the return address off the stack. |

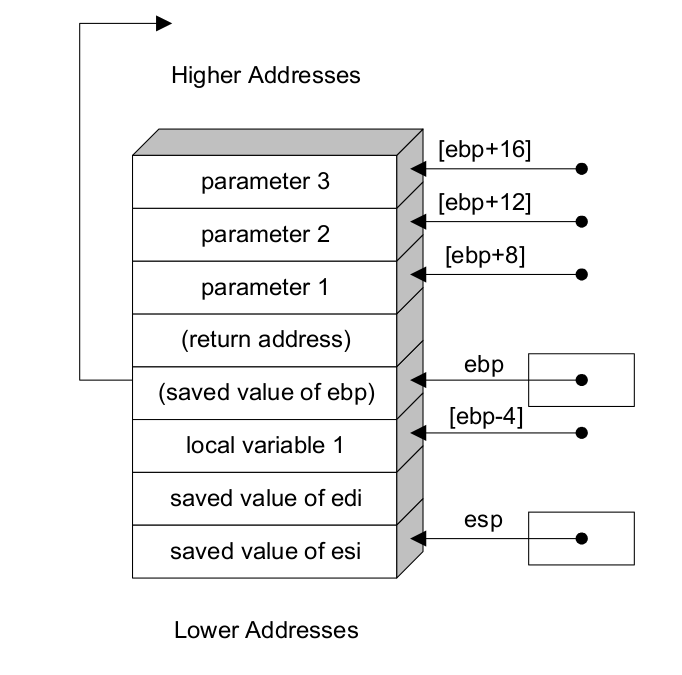

Here we can see how EBP plays the referencing role so well:

Wrapping it up, we have two important references:

- EBP: Having the address of the old ESP, points to the old EBP.

- ESP: Points to the top of the stack.

This was a summary. if you would like to read in more details and examples, here’s the full text.

Buffer Overflow

So let’ do some real work!

Here is narnia0.c:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main(){

long val=0x41414141;

char buf[20];

printf("Correct val's value from 0x41414141 -> 0xdeadbeef!\n");

printf("Here is your chance: ");

scanf("%24s",&buf);

printf("buf: %s\n",buf);

printf("val: 0x%08x\n",val);

if(val==0xdeadbeef){

setreuid(geteuid(),geteuid());

system("/bin/sh");

}

else{

printf("WAY OFF!!!!\n");

exit(1);

}

return 0;

}

What it does? It wants us to change the value of val from 0x41414141 to 0xdeadbeef, if we succeed the program will give us a shell with the narnia1 user access. Sounds good!

Keep in mind that deadbeef is actually a hex value.

Let’s look up the lines each:

Line by Line

- First it defines two variables. val which has a hex value and buf which is an array of characters with a length of 20.

- Prints out messages. Asks us nicely to change the value of val.

- Reads input. The %s character means it’s reading a string, and 24 indicates the input’s length. It’ll put the string in variable buf. You can see the full instructions for scanf here.

- Prints out messages. Shows the contents of val and buf.

- Checks if we did the change, if so delivers a shell with narnia1 user access.

- If not shows a message and exits.

- The End!

Exploiting

The program asks us to enter a string of 24 bytes length.

As we saw in calling convention, when the main function executes, it will allocate some space in the stack for the local variables. Here val and buf.

The point is, buf lies bellow var in the stack. Meaning the address of the buf variable is lower than val. It’s been specified that buf is a 20 bytes size string, but scanf is putting 24 bytes in it, so the remaining 4 bytes will be written into val.

All we have to do is to choose the first 20 bytes as whatever as we want and the next four bytes: 0xdeadbeef.

This vulnerability, which lets us write to some variable with on overflow of a buffer, is called:

Buffer Overflow (da!).

UID

Each user in Unix is associated with a unique number called User ID.

There are three important types of UID defined for a process, let’s have a look at them:

-

Real User ID: For a process it’s simply the UID of the user who has started it.

-

Effective User ID: Normally it’s same as Real UID, but can be changed to enable a non-privileged user to access what can be accessed by the privileged user.

Take a look at passwd:

-rwsr-xr-x 1 root root 68208 May 28 2020 /usr/bin/passwd

The setuid flag is set. So when a normal user runs the binary, the EUID becomes 0 (root’s UID) and RUID remains the same. -

Saved User ID: When a process is running with a privileged access, meaning EUID is changed, and it want’s to do some under-privileged job, the value of EUID is saved to saved user id (suid) and sets the EUID to the non-privileged UID.

Consider again this line in the code:

setreuid(geteuid(),geteuid());

It’ll simply set the values of EUID and RUID of the calling process to it’s Effective User ID, so the process will have the narnia1 user access.

Endianness

-

Endianness is the order to store a sequence of bytes in the computer memory. It is also used in networks for transmitting bytes over a channel.

-

There are two types: big-endian and little-edian. In a big-endian system the most significant byte is stored in the smallest memory address and the least significant byte a the largest. Little-endian is reverse.

-

Big-endianness is mostly used in network protocols and little-endianness in processor architectures (x86, Arm and …) and their associated memory.

So how does little-endian work and benefit us?

In order to store 0xdeadbeef in a memory location, we have to put it in this form: 0xefbeadde.

Why? Because this way 0xde will go into the first byte, 0xad the second, 0xbe third and 0xef in the last byte. This happens because our processor stores the least significant byte in the least significant address, in the memory.

In conclusion our desired string would be looking like this:

12345678901234567890efbeadde

The first 20 bytes filled with whatever we want, and the 4 remaining ones with 0xdeadbeef in the little-endian compatible format.

Subshell

This is the magical command for getting the shell:

(printf "12345678901234567890\xef\xbe\xad\xde"; cat - ) | ./narnia0

-

By putting our command in parentheses we’re executing it in a subshell. This way we have a parallel shell beside the one program is running in.

- We use printf to wrap our string up in the proper format. We don’t want to give deadbeef as a string, but as a hex value, a binary.

- After that we run cat with a dash mark. So when the shell (system(“/bin/sh”)) opens it will constantly get input and deliver to the new born shell.

Congrats! You got the shell, now you just need to use cat for viewing the narnia1 user password from /etc/narnia_pass/ directory.

tags: binary - ctf - rce - reverse-engineering - narnia - wargames

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.